“The places that seem to be the most anxious about immigrants don’t have very many of them,” observed panelist Manuel Pastor. Contact with real immigrants tends to relieve anxiety about imaginary immigrants, noted the USC Dornsife sociologist who heads the Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration.

By Diane Krieger

With Donald Trump in the White House, fear seemed to be on everyone’s mind at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books. At least five panel discussions in Wallis Annenberg Hall featured distinguished USC faculty-authors grappling with the theme.

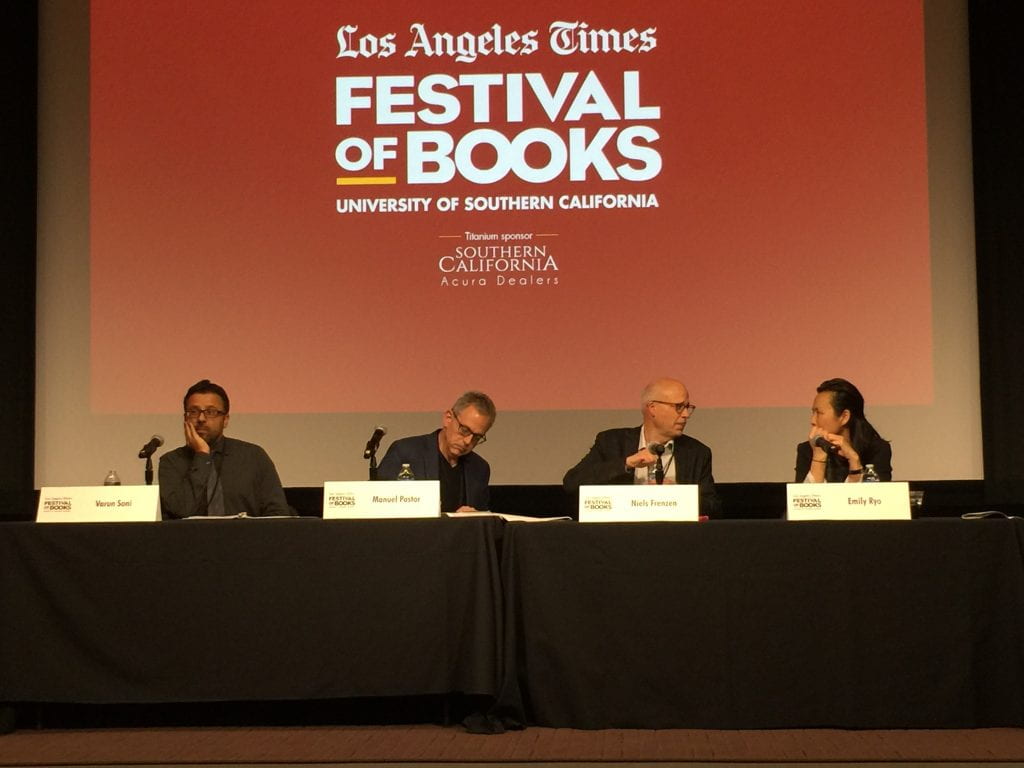

“I see a level of fear similar to what happened in the days and weeks after 9/11,” said law professor Niels Frenzen, in a conversation titled “Walls and Lines in the Sand: The Shifting Landscape of Immigration.” The Saturday noontime panel, moderated by USC Dean of Religious Life Varun Soni, explored the legal status of sanctuary cities and widespread anxiety about deportation in Los Angeles County, where one in ten people are undocumented, and a fifth of all children have at least one undocumented parent.

While the fears of undocumented and “DACA-mented” immigrants are legitimate, said Frenzen, who leads the Immigration Clinic at the USC Gould School of Law, the American heartland’s fear of immigrants is not.

“The places that seem to be the most anxious about immigrants don’t have very many of them,” observed panelist Manuel Pastor. Contact with real immigrants tends to relieve anxiety about imaginary immigrants, noted the USC Dornsife sociologist who heads the Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration.

Undocumented immigrants are “the people who are parking our cars, tending our yards, they’re the people we trust with our most precious commodities in the world—our older adults and our kids,” Pastor said. Fearing them is irrational.

Carrying out Trump’s campaign promise of mass deportations is unrealistic, noted USC Gould’s Emily Ryo. “It’s going to be massively expensive,” she said, costing the federal government up to $600 billion. But Pastor predicted the “deportation sideshow” will remain symbolically important to the administration—helping to mollify a voter base angered by Trump’s failure to deliver on material campaign promises, such as repeal of Obamacare, tax reform and job-producing infrastructure spending.

Fear No Evil

Such cynical “fearmongering” was the focus of another Saturday panel discussion, titled: “What Are We So Afraid Of? The Role of Fear in Our Lives.”

From antibacterial soaps to gated communities, fear sells products, explained sociologist and former USC executive vice provost Barry Glassner, author of the best-selling book “The Culture of Fear: Why Americans Are Afraid of the Wrong Things.” There’s nothing new about politicians ginning up fear for political advantage. Like a magician’s “misdirection,” they use fear to conceal some sleight of hand, said Glassner, who is himself an accomplished magician.

Joining him on the panel was University Professor Leo Braudy, holder of the Leo S. Bing Chair of English and American literature at USC, and the author of “Haunted: On Ghosts, Witches, Vampires, Zombies, and Other Monsters of the Natural and Supernatural Worlds.”

“All monsters are multipurpose metaphors for what we’re afraid of,” Braudy said. Our postmodern fixation on zombies is particularly revealing, he argued. Today we are less afraid of “king vampires” like Dracula than we are of leaderless malignant groups. “Zombies are not individuals; it’s a horde that we don’t like and are fearful about.”

From the 1970 to the ’90s, Americans irrationally feared white suburban teenagers, noted Glassner. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the “sick society” narrative shifted and “the new villains were from foreign lands, not domestic.”

Fear the Fake News

A third Saturday panel, “Truth Matters: Media in the Age of Fake News and Alternative Facts,” looked at what journalists can do to diffuse fear-driven hysteria and counter lies that spread like wildfire on social media.

Moderator Marty Kaplan, director of USC Annenberg’s Norman Lear Center, threw his faculty panel unsettling questions such as: “What if the news media have become pawns in a big chess game of information war?”

Social and political historian Steven Ross took solace in precedent. “The information wars have been going on forever,” said the USC Dornsife professor, who directs the USC Casden Institute for the Study of the Jewish Role in American Life.

When the first nickelodeons opened in in 1905, Ross noted, “legitimate media attacked that new form of communication. Why? Because radical filmmakers like Charlie Chaplin were suddenly communicating with tens of millions of people, and it freaked out the establishment.”

Social media is no different: a new form of mass communication bypassing traditional authorities, he said.

But unlike previous media breakthroughs, we’ve entered “a new era where the audience is a big player,” countered award-winning correspondent and Annenberg professor Judy Muller. Instead of consuming news, everyone is now a “pro-sumer”—both consuming and producing content by sharing and reposting.

The media education of the pro-sumer should be an urgent priority, Muller contends. “Start in the first grade with news literacy programs. Right now!” she said. “We can’t have a functioning democracy with people only believing the lies they want to believe,” added Muller, who covered the Rodney King and O.J. Simpson trials for ABC and is a regular contributor to NPR’s Morning Edition. “We should all be detectives.”

The threat to journalism transcends Donald Trump’s oft-tweeted “alternative facts,” argued USC Annenberg’s Diane Winston. “It’s the economic system we live under: The news is always hemmed in by multinational structures and the corporations that control it.” Nonprofit models would be more compatible with truth-seeking, Winston believes, though as an expert in media and religion, she shuns the spiritually loaded word “truth” and prefers calling it “fact-based” reporting. Ultimately, Winston believes the antidote to fake news and partisan information silos lies in narrative storytelling. “It’s ironic that I’m a journalist and a historian, and not a screenwriter,” she said. “But I think stories are the way to go.”

Fear was in the air again on Sunday, as USC faculty focused on more Trump-induced anxieties. Annenberg arts journalism educator and dance critic Sasha Anawalt moderated a conversation titled, “Is This Goodbye, NEA? Addressing Our Fears — and Hopes — for the Arts and Humanities.” Faculty panelists included Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Viet Thanh Nguyen, a professor of English and American studies and ethnicity, and actor-director Anita Dashiell-Sparks of the USC School of Theatre.

Also on Sunday, USC Annenberg’s K.C. Cole moderated “From Protest to Action to Justice: Politics, Media and the Law,” with fellow Annenberg professor Robert Scheer, and USC Gould professors Jody Armour and Gillian Hadfield.